In Himachal Pradesh the last camps of the nationwide Summer Camp program were running. When I found out a team from Delhi was going to Himachal Pradesh to assess the Summer Camps I decided to join them and see what had been happening in this part of the country. Walking in Himachal Pradesh feels like taking a stroll through a Hindi movie love scene. There were flowers everywhere, and trees heavy with fruit were rustling overhead. The humidity was low and it wasn’t too hot – a blessing after the stifling Delhi weather – and when the clouds came in they wrapped the mountainside in a thin layer of mist and it would drizzle lightly. The mountains rose steeply behind us, but a wide fertile valley opened in front, speckled with paddy fields and winding rivers. Two block coordinators Anuradha and Sangeeta were accompanying us and together we made a merry team, chatting and laughing as we walked.

On the road to one of the camps we paused for a lunch of Sangeeta’s home grown mangos. They were small and yellowish on the inside – but so sweet! Juice ran down our face and hands as we slurped the delicious mango. We were visiting a village built on a tongue of land between two rivers that flood during the monsoon months, making the village inaccessible. We sat eating our mangos on the ridge of the riverbank, overlooking a valley that looked as though it had been untouched for hundreds of years. The village was very picturesque; the buildings were painted in rustic shades of indigo and green and in the cool shade of the verandah were wicker baskets for grain storage. Majestic roosters strutted in the lanes and lines of colorful washing were strung between the trees.

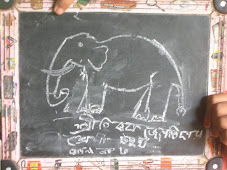

The school was set slightly apart from the rest of the village, standing alone on a small raised area. One room of the school had been opened for the summer camp, and inside we found thirty little faces sitting in their ability groups. Four young volunteers were waiting expectantly for us. It was dark inside the classroom, and I noticed a heap of rubble in one corner. One of the volunteers was newly married, still wearing her bangles and with henna on her hands. She was a little nervous, showing us how she had been using the summer camp material and calling the children up to recite songs and poems for us. There was a wide range of ages and abilities in the classroom. I tested some of the children in the ‘nothing’ group – children who had started the summer camp unable to recognize letters and numbers – and noted that they were all able to read alphabets in Hindi and calculate simple addition and subtraction, although some of the children were so shy that their answers were hardly audible. Some of the older children enjoyed playing with the currency Pratham had prepared for the summer camp. Using notes of 1, 10, 100 and 1000 the children were able to play games while practicing their mental arithmetic skills.

After visiting the school, we went to the home of one of the volunteers for tea. The summer camps had clearly been received well in this village – children had maintained or improved on their learning levels, and the volunteers told us about a rally that they held with the children to cement community support and enthusiasm. Anuradha and Sangeeta had taken the camp children on a picnic – an enormous treat for the children and their families. As we sat and chatted, a few curious children were peeping out of the windows and the sides of the buidings. It started to rain. We all sat around together, sipping our tea and watching the rain.

______________________________________________________

www.readindia.org

www.pratham.org.uk

www.prathamusa.org

www.pratham.org

Sunday, August 17, 2008

Tuesday, August 12, 2008

Back in Delhi

Recently, data collected by the East Delhi office showed that the area still has a large number of children (c.11,000) who attend neither government school, nor Pratham’s direct (community-based) program. I spent two days in the field finding and interviewing some of these children in order to understand more about their circumstances and see how Pratham can better target this elusive group.

Visiting those bastis is something I shall never forget. The lanes were dark, narrow and filthy with open gutters, flea-ridden animals and the insects swarmed so thickly they hung like a veil across my path. The overcrowding was intense: families of five to six lived in rooms so small that I could cross them in a single stride and the smell was overpowering. Today we visited a basti in which Pratham does not operate a direct program. We asked the children whether they knew of Pratham and asked them about their levels of education, if any. We visited during school hours in the hope of catching the non-attendees at a time when parents might be at work (and children more able to answer our questions freely). We spoke to three families. In each case, we found young girls of about twelve to fourteen years at home with infant siblings, of which there were normally two or three. All three girls had lost their mothers. They told us that their fathers and brothers (often of about the same age) were working in factories making plastic home-wares such as tea strainers, or ironing and pressing clothes, and pulling rickshaws. Two girls told us that their brothers were able to read and write, although none of them had studied beyond third standard.

We had anticipated that children might have been working instead of going to school. We also suspected that many out of school children would be migrants – and they were – but not quite in the way we had expected. Many migrant families came to Delhi from rural areas for work, sometimes children came to the cities alone. Furthermore, seasonal migration prevents children from finishing their school year in the same place that they started. Today we discovered a further nuance to the problem of migration: many families and especially newly arrived migrants were constantly on the move, changing room every couple of months. But if the family moved out of their school catchment area, then the child would have to move to a new school. The process of re-enrollment was highly problematic and often children would be shut out of the school system till the beginning of the next academic year. Another girl explained that she tried to enroll her young brother in first standard, but he was ill with tuberculosis during the enrollment period. In fact, he was still weak and not yet fully recovered, and she said she would try to enroll him again next year.

The children talked of other barriers to education: the associated costs of school (school uniform, birth certificates etc) were too high, and fears of allowing children to walk to and from school alone. However, there was strong support for a direct program and general desire to attend school was high. It was interesting for me to be able to see the thorough planning and data collection process, to view the questionnaire design and the uninhibited interaction of the Pratham staff with the community. Pratham’s interventions thrive on community support and public will to bring about change, especially in the face of government underprovision. I left the field feeling happy and optimistic that before even establishing a presence in the basti, Pratham’s staff were excellent ambassadors for the cause and had sewn the first seeds of a good future relationship with the people we met today

______________________________________________________

www.readindia.org

www.pratham.org.uk

www.prathamusa.org

www.pratham.org

Visiting those bastis is something I shall never forget. The lanes were dark, narrow and filthy with open gutters, flea-ridden animals and the insects swarmed so thickly they hung like a veil across my path. The overcrowding was intense: families of five to six lived in rooms so small that I could cross them in a single stride and the smell was overpowering. Today we visited a basti in which Pratham does not operate a direct program. We asked the children whether they knew of Pratham and asked them about their levels of education, if any. We visited during school hours in the hope of catching the non-attendees at a time when parents might be at work (and children more able to answer our questions freely). We spoke to three families. In each case, we found young girls of about twelve to fourteen years at home with infant siblings, of which there were normally two or three. All three girls had lost their mothers. They told us that their fathers and brothers (often of about the same age) were working in factories making plastic home-wares such as tea strainers, or ironing and pressing clothes, and pulling rickshaws. Two girls told us that their brothers were able to read and write, although none of them had studied beyond third standard.

We had anticipated that children might have been working instead of going to school. We also suspected that many out of school children would be migrants – and they were – but not quite in the way we had expected. Many migrant families came to Delhi from rural areas for work, sometimes children came to the cities alone. Furthermore, seasonal migration prevents children from finishing their school year in the same place that they started. Today we discovered a further nuance to the problem of migration: many families and especially newly arrived migrants were constantly on the move, changing room every couple of months. But if the family moved out of their school catchment area, then the child would have to move to a new school. The process of re-enrollment was highly problematic and often children would be shut out of the school system till the beginning of the next academic year. Another girl explained that she tried to enroll her young brother in first standard, but he was ill with tuberculosis during the enrollment period. In fact, he was still weak and not yet fully recovered, and she said she would try to enroll him again next year.

The children talked of other barriers to education: the associated costs of school (school uniform, birth certificates etc) were too high, and fears of allowing children to walk to and from school alone. However, there was strong support for a direct program and general desire to attend school was high. It was interesting for me to be able to see the thorough planning and data collection process, to view the questionnaire design and the uninhibited interaction of the Pratham staff with the community. Pratham’s interventions thrive on community support and public will to bring about change, especially in the face of government underprovision. I left the field feeling happy and optimistic that before even establishing a presence in the basti, Pratham’s staff were excellent ambassadors for the cause and had sewn the first seeds of a good future relationship with the people we met today

______________________________________________________

www.readindia.org

www.pratham.org.uk

www.prathamusa.org

www.pratham.org

Saturday, August 9, 2008

There are two forces invading the Bihari countryside: Pratham, and Amul Macho Male Innerwear (crafted for fantasies, of course).

Business as usual: elephant and camel in near miss with large truck

Bihar is lush and fertile: we were flanked by lychee orchards, banana groves, watermelon, rice and wheat fields all the way to Bettiah. Everything was so green I needed sunglasses to look out the window. At the same time, the poverty is severe and institutionalized, and it was fascinating for me to spend fourteen hours in conversation with people who are helping Bihar move in strides towards development. While there had been no teacher recruitment in Bihar for fifteen years, in 2005 the state government recruited 85,000 new teachers and Pratham designed and implemented the teacher training program. A further 115,000 teachers have been recruited since.

Once in Bettiah, it was truly exciting to see this in action: the very purpose of our trip was to oversee a workshop that was training project monitors to measure the impact of Read India properly. Leading the training were three very impressive young women: Afsha, Heena and Paribhasha. They were feisty and bright, and I couldn’t help but smile at the way the three young women were confidently commanding the attention and respect of fifty men. This was another opportunity for me to marvel at the incredible people that Pratham attracts and grooms. I also found the training interesting for two reasons: firstly, I enjoyed learning about the project testing methods. I was curious to know how the impact of Read India could be measured and evaluated. Secondly, this was my first direct exposure to the research and development side of Pratham. Pratham has a rigorous system of evaluating its impact, both at the point of designing program content and (like today) in order to evaluate the success of a program . This seemed such efficient cycle: Pratham’s literacy programs teach children faster than ever because materials are built exclusively around material that children respond well to, as determined by continuous investigation.

Most of my weekend was spent on a colossal commute across Bihar: from Patna to Bettiah. I clattered down an old and deeply pot-holed lane/main road for seven hours in each direction on a visit to the Read India evaluation site. Luckily, with my eclectic group of companions and Amul adverts, the time flew by. (Enter Rukmini Ma’am, leading the charge with Michael Walton, an extremely well traveled Englishman and professor at Harvard; Mark, the Garba aficionado, Adrien, the nearly Bhojpuri film star, and me, trying not to think about sudden death by oncoming traffic).

Business as usual: elephant and camel in near miss with large truck

Bihar is lush and fertile: we were flanked by lychee orchards, banana groves, watermelon, rice and wheat fields all the way to Bettiah. Everything was so green I needed sunglasses to look out the window. At the same time, the poverty is severe and institutionalized, and it was fascinating for me to spend fourteen hours in conversation with people who are helping Bihar move in strides towards development. While there had been no teacher recruitment in Bihar for fifteen years, in 2005 the state government recruited 85,000 new teachers and Pratham designed and implemented the teacher training program. A further 115,000 teachers have been recruited since.

Once in Bettiah, it was truly exciting to see this in action: the very purpose of our trip was to oversee a workshop that was training project monitors to measure the impact of Read India properly. Leading the training were three very impressive young women: Afsha, Heena and Paribhasha. They were feisty and bright, and I couldn’t help but smile at the way the three young women were confidently commanding the attention and respect of fifty men. This was another opportunity for me to marvel at the incredible people that Pratham attracts and grooms. I also found the training interesting for two reasons: firstly, I enjoyed learning about the project testing methods. I was curious to know how the impact of Read India could be measured and evaluated. Secondly, this was my first direct exposure to the research and development side of Pratham. Pratham has a rigorous system of evaluating its impact, both at the point of designing program content and (like today) in order to evaluate the success of a program . This seemed such efficient cycle: Pratham’s literacy programs teach children faster than ever because materials are built exclusively around material that children respond well to, as determined by continuous investigation.

______________________________________________________

www.readindia.org

www.pratham.org.uk

www.prathamusa.org

www.pratham.org

www.readindia.org

www.pratham.org.uk

www.prathamusa.org

www.pratham.org

Saturday, August 2, 2008

The world's best byriani

When I arrived in Hyderabad, the team, along with Kishor Sir from Mumbai and the PCVC (Pratham Council for Vulnerable Children) were designing a survey to estimate the number of children in ‘visible’ employment – shops and restaurants – in commercial areas of Hyderabad. The pilot would be relatively simple. We decided to head towards Charminar, the symbolic fortress in the middle of Hyderabad’s old city, and our task was to record the name of every fifth shop, and whether or not we could spot any children at work inside.

The adventure began in Parveen Ma’am’s home. Fragrant and light, her home made Byriani was cooked to perfection. We sat like a pack of lions around the pots of food and indulged.

Four servings of Byriani later, the team was raring to go. And we needed the sustenance. Charminar was brimming, bustling, bursting with traders, customers, onlookers, tourists, passers by, pedestrians, vendors, scooters, autos, cars, buses, cycles, cows, dogs, cats, dust, smells, food, litter – humanity in all its variety was out in force and in a hurry when we arrived to survey at Charminar (needless to say, I was looking both incongruous and clumsy trying to juggle an umbrella, clipboard and pen and stay with the group in the middle of all this). The team split at Charminar: one team took the route to Madina through the pearl shops, another went to Purana Pul, and my team took on Ladh Bazaar and the bangle markets (this was very considerately organised so that I could roll sightseeing, bangle shopping, and surveying into one exercise).

The market was dazzling. Thousands of shimmering bangles were rustling and twinkling on the stall racks in every kind of size and colour, every thickness and pattern. Yet I astounded myself by getting so engrossed in the survey work that I forgot to buy bangles. The action on the street was much more interesting. We discovered not so many children working inside the shops, but many of them mingling independently on the street, selling handkerchiefs, safety pins, string, shoelaces. The kids were like firecrackers: bright, uninhibited and feisty.

‘Are you going to school?’ Kishor Sir asked one young boy, Secunder.

‘No, but why should I go to school? I earn 200 rupees per day.’

Our young friend had a point. 200 rupees was indeed a lot of money, especially in the hands of a ten year old.

‘Do you know many children who do the same work as you?’

‘Oh yes, I know all the kids. There are around five hundred in this area and we all get our goods from Firoz Bhai.’

‘Firoz Bhai??’ We leaned in, clipboard at the ready, to hear what else Secunder was going to tell us.

‘Yes! Let me take you to him! You have to meet him.’

The next thing we know, Firoz Bhai is explaining that if we want to educate these children we have to ask them if they want to go, because he only sells goods to them, the children do not work for him. Secunder, meanwhile, is energetically assuring us that school is a good idea, and he will not only find a room for us to hold classes but that he will also round up all the children working in the area and get them to attend.

When we later retold this story to everyone over some fresh samosas at Sunita Ma’am’s house, we discovered the others had also had similar encounters. Together we had spotted over 200 children in the Charminar area. I left Hyderabad just as Kishor Sir and his team were rolling up their sleeves to find out more.

______________________________________________________

www.readindia.org

www.pratham.org.uk

www.prathamusa.org

www.pratham.org

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)